CAD Report: Whatever happened to…?

By Ralph Grabowski

CAD/CAM/CAELessons learned from the CAD industry’s wrong turns of the past.

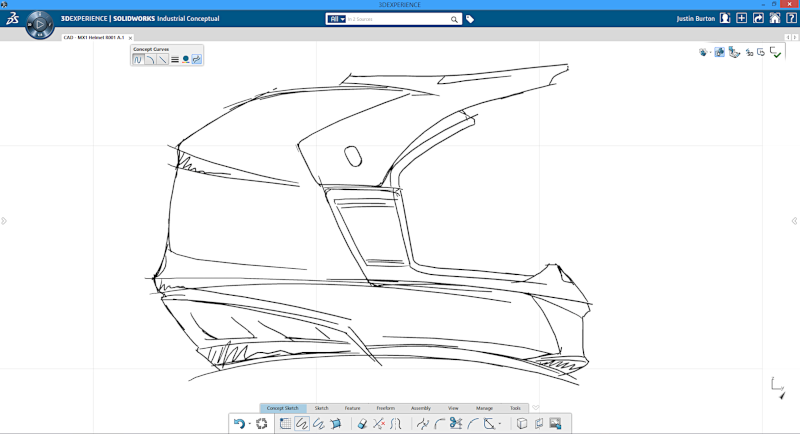

Sketching a new helmet design with Solidworks Industrial Designer

(Photo credit: Dassault Systemes)

For some CAD vendors, the tides of time wash away the plans for their future, no matter how well-executed. In 38 years of writing about computer-aided design, I’ve seen numerous companies disappear, perhaps through acquisitions, or else crushed by competitors, and even through pivots by the market.

Some – like the nVidia of the 1980s, Artist Graphics – were the giants of their times who threw the biggest parties at CAD conferences. My favorite: The long desert-only tables served on the Queen Mary. Today, the Internet has almost no record of that company from Minneapolis that invented the first proprietary graphics chip.

So, why should we care about companies that no longer exist? Failure does a better job of teaching us lessons than successes do. The outcome of failure helps guide our thinking on the probable trajectories of today’s hot-or-not technology. It also helps us look past the marketing reassurances that these newly-launched products are the most important things ever. Until they’re not.

Let’s look at the trajectories taken by several different CAD products.

Rejection: Artist Graphics

The first personal computers had miserable graphics, with the original IBM PC offering just 640×480 resolution in a single color. The huge demand from CAD users for huge resolution led to companies like Artist Graphics, Nth Graphics and Vectrix making fistfuls of money selling high-end boards at an inflation-adjusted equivalent today of $10,000 and more.

Worse, each monitor had to match each graphics board’s sync exactly, making both of them proprietary: Changing the graphics board meant spending another couple thousand on another matching monitor. The game collapsed when NEC released the first multi-synchronization monitor. Then, companies like nVidia and ATi (today AMD) emerged to offer low-cost graphics boards and the switch to software-based display-list processing. Artist Graphics spent too much developing their next-generation graphics chip and by 1995 became bankrupt.

Lesson Learned: Being first and holding the best parties doesn’t preserve your place in the market. Stay paranoid by viewing your competitors as better than yourself, and by maintaining a keen awareness of changes happening to your market.

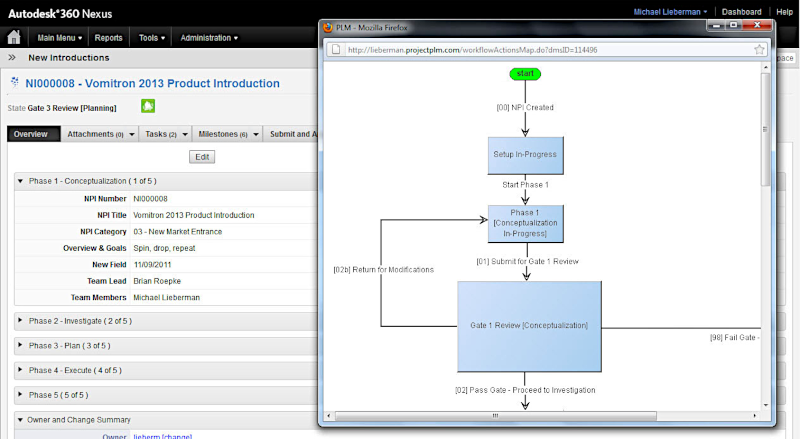

Reinvention: Autodesk Nexus PLM

Carl Bass, who was CEO of Autodesk in the years around 2010, considered PLM a joke, initially. Product lifecyle management had been invented by large CAD vendors to get customers to pay for a lifetime of software and services, well beyond the purchase of only drafting programs.

In 2011, Mr. Bass changed his tone. Autodesk would have PLM, it would be cheap, run on existing Vault data management software, share data through the online Buzzsaw application, ensure zero customization through hundreds of specialized modules, and be named “Autodesk Nexus 360 for PLM.” As Autodesk saw it, this was in tune with what customers wanted.

Administrator graphically customizing a workflow in Autodesk’s Nexus 360.

(Photo credit: Autodesk)

Lesson Learned: What companies think precisely fits the need of customers is not necessarily what customers think they need. When you get it wrong, the product can be corrected, but at the price of customer confusion over product naming and capabilities. And so to this day, Autodesk is a smaller PLM player relative to its size in the CAD market.

Misdirection: Solidworks Mechanical Conceptual and Industrial Designer

Dassault was smart when in 1997 it paid $310 million to acquire Solidworks. It became the world’s most popular MCAD program, today generating over a billion dollars a year in sales. For a long time, Dassault left Solidworks alone, but then those millions of users became too tempting a target to ignore. They needed to become users of Dassault’s own software, because it cost more, and more cost equals higher revenues.

In 2013, Dassault introduced Solidworks users to the first two programs based on its own software: Solidworks Mechanical Conceptual and Solidworks Industrial Designer. Despite the name, the two had nothing to do with Solidworks, and were based on technology inherently incompatible with Solidworks.

Dassault spent the next decade repeatedly reintroducing variations of its software to the collective yawns of users, and always appending the Solidworks name, such as this year’s Collaborative Designer for Solidworks. How collective is the yawn? So far, 3% of Solidworks users have taken up Dassault’s offerings.

Lesson Learned: Spending a decade unsuccessfully pressing your round peg into an acquisition’s square hole means it’s time to concede. Either spin off that balky acquisition, or else make it a fully independent subsidiary.

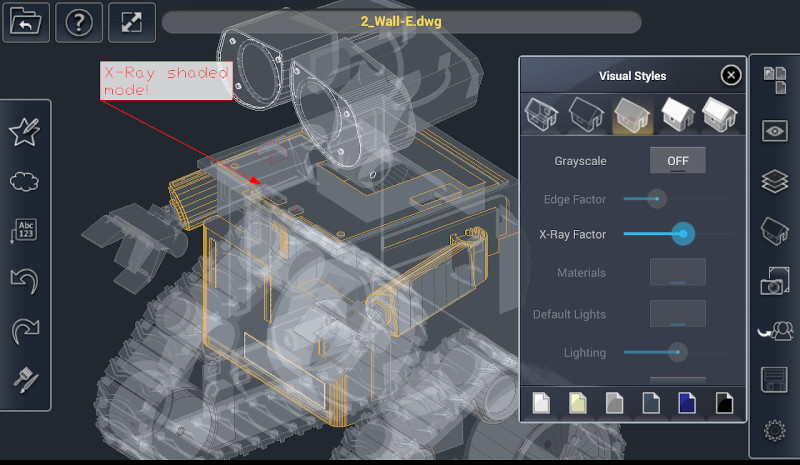

Misapplication: Mobile CAD Apps

Following the launch of iPad in 2011, the future of CAD was to run it on smartphones and tablets, clearly. We would now carry all our drawings with us; it was the end of paper in the field! After all, games and texting worked so well that they were becoming addictive. But not so for CAD.

IMSI’s mobile app, TurboViewer, debuted in the mid-2010s as part of the company’s $999 TurboApp package.

(Photo credit: IMSI)

There were also problems with limited RAM, the lack of on-board vector processing and mud-unfriendly hardware. To customers, the value of mobileCAD came close to zero; developers couldn’t sustain themselves on nearly-zero income. Companies dropped out; as the CEO of a competitor told me, “Why should we bother writing a DWG app when Autodesk already did it for us?”

Today, the CAD apps that remain are free, ad-supported or else bundled with annual subscriptions of desktop software.

Lesson Learned: It takes time to understand how new technology doesn’t necessarily suit your vertical market. Today, everyone can be a first-mover with all the programming assistance available, so it pays to hang back and observe the impact of new tech on your competitors.

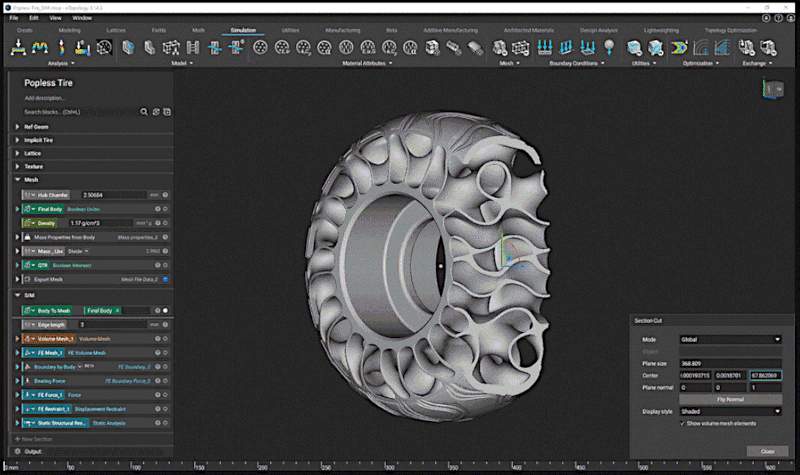

Misjudged: Generative Design

Probably the most exciting technology in CAD has been generative design, which does what humans cannot: Output designs optimized for today’s resource-limited world. This, surely, ought to be in every engineer’s toolbox. Except it’s not.

There are independent firms that offer the software (such as nTopology), and CAD software giants that offer it at extra cost. But when we look about, we don’t see its results in new products. It’s invisible.

Optimizing an airless tire design with nTopology’s nTop software.

(Photo credit: nTopology)

Lesson Learned: Customers may not appreciate otherwise-cool technology that adds extra steps and extra cost to product development. A certain level of design inefficiency is tolerated by the market.

These examples from history tell us about the future of new technology like AR/VR/XR/MR, AI, NFT, and DeFi. There is an initial exploration phase, in which all kinds of companies work to see how the tech fits: Firstly in their marketing plans, and then secondly into their products. Money is spent; money is lost.

The lesson is that new technology, which initially seems to overwhelm the world with its inevitability, always goes in one of two paths: it becomes an along-side technology, or it disappears. As I write this, corporations are going nuts over AI; eventually, it will fade into the background like the Internet itself, or else fall away like NFTs.

Ralph Grabowski writes on the CAD software industry on his blog (www.worldcadaccess.com) and has authored numerous articles and books on CAD.