End-of-life Design

Mike McLeod

SustainabilityDiverting e-waste from local landfills and toxic “backyard” operations in developing nations begins with product designers.

Despite increasing public awareness and international treaties banning the export of e-waste to developing nations, the amount of discarded computers, TVs, cell phones and other electronic garbage finding its way to other countries continues to increase annually. According to the United Nations, approximately 46 million tons of electronics were discarded globally in 2014, an amount estimated to grow to 50 million by 2018. Of that 46 million, the U.S. accounted for more than 7.7 million tons, while Canada, by comparison, generated 725,000 tons.

The good news is that initiatives to divert e-waste from local landfills, at least in Canada, are pushing public behavior in right direction. According to Statistics Canada, the majority of Canadians dispose of electronics via donation, returning it to the supplier or taking it to drop-off centers or depots; a small percentage simply include it in their regular garbage.

The bad news is that relatively few Canadian landfills ban e-waste outright. Only Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland have banned e-waste from landfills province-wide while the majority British Columbia and Ontario landfills have a ban in place. Conversely, no landfills in Alberta, Quebec, Manitoba and nearly all of Saskatchewan ban e-waste dumping. As a result, more than 140,000 tons of e-waste finds its way to Canadian landfills each year, according to Shift Recycling, one of the major e-waste recycling companies in Ontario. In addition, only 20 percent of e-waste generated annually in Canada is collected by e-waste recyclers as many household simply hold onto old computers, monitors, cell phones etc. than get rid of it.

Worse still, even if people properly dispose of their e-waste, it still finds its way to developing nations, where rudimentary salvaging operations expose workers and communities to high levels of toxicity. According to the Basel Alliance Network (BAN)–a non-profit watchdog organization named for the United Nations Basel Convention that restricts the trade of hazardous waste – approximately 50 percent of e-waste generated in the U.S. and Canada ends up in unregulated “backyard” operations in countries like Kenya, India and China.

During a “sting” operation conducted by BAN between July 2014 and February 2016, the organization followed the journey of 205 electronic items from initial drop-off at recycling centres to their final destinations. GPS tracking devices hidden in these e-waste items revealed that 66 of them (32 percent) were exported illegally. In total, 27 presumably “responsible” recyclers, including one certified by BAN’s own e-Stewards program, exported e-waste to countries where importing it from the U.S. is illegal.

Those in the industry say the reasons for this are purely economical. Although provinces have implemented extended producer responsibility (EPR) programs, with their associated point-of-purchase eco-fees designed to off-set the cost of recycling, disreputable brokers profit more by exporting e-waste to the U.S. According to reputable firms like Shift Recycling, it’s approximately 10 times cheaper to export e-waste than to dispose of it domestically.

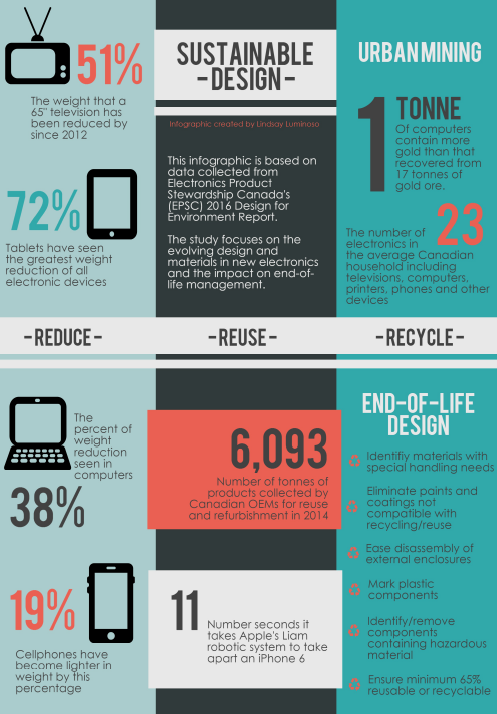

Part of the solution, says the Electronics Product Stewardship Canada (EPSC), is reducing the costs associated with recycling end-of-life electronics. In its 2016 Design for Environment Report, the industry-led not-for-profit organization says cost reduction begins with designers. Its members are taking steps to reduce and recycle their electronic products from the outset.

For example, the report says that, between 2009 and 2016, the weight of the average 65-inch TV has decreased by 51 percent. Similarly, the material footprint of desktop computers has gone down by 37 percent, printers/copies by 45 percent and computer monitors by 60 percent.

More importantly, the organization points to initiatives within member companies to implement design principles that make it easier to dismantle end-of-life electronics. For example, Cisco stipulates that all mechanical parts greater than 100 grams consist of one material and that all plastic parts more than 25 grams be material coded and therefore easily identified by recyclers.

Similarly, Dell restricts their suppliers in the use of metallic or galvanic coatings and specifies that plastic parts over 100 grams can’t contain paints or coatings that aren’t recycling compatible. As part of its design guidelines, HP recommends that snap-in features and common fasteners be used in place of adhesives where possible and that plastic and metal parts be easily separable.

In addition, the report says companies are opting for higher levels of recycled plastic in newly manufactured equipment. PC-maker Lenovo, for example, says it has used more than 55 million pounds of post-consumer recycled content (PCC) plastic in its new notebooks, workstations and monitors since 2005. Samsung has increased use of recycled plastic in all its products to 5 percent while Sony says that 76 percent of the plastic used in one of its latest hand-held cameras was recycled material.

While encouraging, these efforts are relatively small compared to the sheer volume of e-waste being produced globally. In the near term, large e-waste producers and exporters like the U.S. will have to strengthen national and state laws that let e-waste slip through. In the meantime, designers can do their part to ensure there is more profit in responsibly dismantling end-of-life products than dumping it on poorer countries.