The highs and lows of CAD since the 1970s

By Ralph Grabowski

CAD/CAM/CAETracing the evolution of computer-aided design since the 1970s, from microcomputers to the cloud.

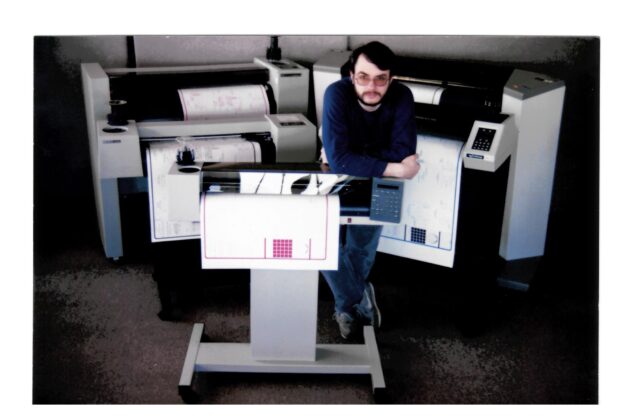

March 1988: Ralph Grabowski reviewed five pen plotters, showcasing cutting-edge drafting technology of the era. Back: HP DraftMaster II and Bruning ZetaDraft 900. Middle: HP DraftPro, CalComp 1023. Front: Enter Computer SP1800. (Credit: Ralph Grabowski)

CAD for personal computers first emerged in the late 1970s. The first microcomputer (as they were then called) was 1975’s Altair 8800, which you had to solder together and then program by flipping toggle switches on a front panel. It cost $2,700 in today’s dollars.

The lure of the microcomputer was strong. It promised us freedom from time-shared (and cost-shared) mainframes and mini-computers. The promise unleashed a pent-up demand that encouraged entrepreneurs to quickly advance the technology, and by the late 1970s, we could buy computers that looked like today’s. Some even came with applications more useful than the inevitable Space Invaders game.

But this unleashing had a downside. There were so many brands and standards that we became wary of jumping in; we might get stuck with an expensive asset that might prove to be a dead end. My first microcomputer in 1983 was a not-quite-IBM-compatible one that cost $12,000 (with dual floppy drives) in today’s dollars—and it went obsolete two years later.

The standards mess ended in August 1981 when IBM introduced its PC (short for “personal computer”). It was relatively expensive, but it was (somewhat) open, and because it was from IBM—the most important computer company at the time—it immediately set the standard on which we continue to operate computers today: BIOS, ISA bus, VGA graphics, Ctrl+Alt+Del, Intel CPU, DOS/Windows and so on.

IBM introduced its Model 5150 PC in August 1981, which set the standard on which we continue to operate computers today. (Credit: Ellinor Algin 2007/Tekniska museet)

The start of PC-based CAD

CAD software for PCs began the same way.

In the late 1970s, lots of 2D CAD programs emerged from small companies, each one incompatible with the next. I think the very first one was eventually named VersaCAD. Unlike computer hardware, prices could be quite cheap, starting at $100 for a decent 2D drafting program like Generic CADD.

By the mid 1980s, CAD vendors were vying to be No. 1. VersaCAD had the advantage of being first. Architecturally oriented DataCAD was endorsed by the American Institute of Architects. Mechanically oriented CADkey offered true 3D.

But it was AutoCAD that took the lead—even though it wasn’t first, wasn’t endorsed by any organization and most certainly wasn’t 3D. But what it had was customization. Buyers of the $1,000-program could make it work the way they worked in their niche industries, a concept unique for the times.

As with IBM’s somewhat-open PC, Autodesk’s somewhat-open AutoCAD meant that people could buy with confidence. By the late 1980s, the industry began its first attempts at standardizing on AutoCAD’s file formats so competitors could lure away customers. First with Autodesk’s open ASCII DXF format (the attempt failed) and then with the closed binary DWG format, which succeeded. Later, the building industry standardized on IFCs (industry foundation classes), a metadata exchange format devised by Autodesk with AutoCAD R13.

A Dutch company, Cyco International, was the first to figure out how to read DWG files, and so for the first time, we no longer needed to buy AutoCAD to view and print drawings. The first non-Autodesk program that used DWG as its native file format was 1996’s Vdraft from tiny software firm Softsource, followed two years later by IntelliCAD, which made DWG universal. Competitors rushed to add DWG read-and-write capabilities to their CAD programs, whether a $20,000 Catia system from France or a $0 FreeCAD from a community of enthusiasts.

This is an example of the user interface of AutoCAD Release 12, which came out in June 1992. (Credit: Ralph Grabowski)

Overcoming the big slog

We could run CAD on microcomputers —hurrah!—but it was slow. Painfully slow. At first, a single zoom or pan of the famous Nozzle drawing took five minutes. Adding Intel’s extra-cost numeric co-processor chip ($1,300 in today’s dollars) to the computer reduced the wait to a mere 30 seconds.

The breakthrough came in 1986 with AutoCAD v2.5’s near-instant zooms and pans through software-based display-list processing and the (for the times) hyper-fast 80386 CPUs. I recall an Autodesk salesman boasting that if you looked too closely to the screen, the speed would cut your nose right off.

CAD on our little computers started off cheaply enough, compared with industry giants ComputerVision and Integraph, who sold their proprietary turnkey systems for $100,000 or more per station. But then CAD on our little computers became expensive, as vendors raised prices with each new release and as we added hardware peripherals. We deployed pen plotters to produce paper copies of our electronic drawings, and the very best one—the fastest and most accurate HP Draftmaster—cost $45,000 in today’s dollars. About half as expensive were large 19-inch, high-resolution (1024×768) monitors with dedicated graphics boards, but even more expensive were high-speed, large-format scanners. That thousand-dollar PC CAD program could become a $100,000 system rather quickly.

A CAD manager told me how he afforded those prices. When times were good, he would buy more CAD equipment. And when times were bad, he’d lay off some drafters and then use the savings to buy more CAD equipment. The PC CAD industry to this day never felt a recession—something I can vouch for. During my 39 years writing about CAD, I experienced none of the slowdowns that took place in the general economy.

The Windows awakening

CAD programs first ran on Unix, on DOS or on proprietary operating systems, which limited their capabilities. Unix was user-hostile; DOS was neither multi-user nor multi-tasking (and stingy on memory); and proprietary systems bled customers dry.

The solution emerged from Xerox’s research lab in Palo Alto CA: the WIMP interface—windows, icons, menus, pointer—which was firstly popularized by Apple in its Lisa operating system, and then by Microsoft in Windows. WIMP removed the earlier barriers, giving us user-friendly, multi-user, multi-tasking operating systems that handed applications near-unlimited amounts of memory with which to work.

But WIMP was such a new paradigm that the CAD industry was reluctant to embrace it, though not surprisingly so. Windows was initially CAD-hostile. I recall being flown by a CAD vendor to its headquarters to explain “how Windows works.” It took a decade before SolidWorks 95 showed that advanced CAD could run on Windows quite well. But what made CAD plausible on Windows had nothing to do with CAD.

Early on, Microsoft chased gamers, doing what it took to make 3D interactive games run smoothly (through high frame rates). We in the CAD world got a free ride on the coattails of gamers, because those advances helped make our 3D interactive design software run smoothly. Today, we effortlessly engage in real-time rendering and benefit from instant drafting previews (like hatch patterns and fillet operations).

The march of technology

Within a decade, Windows and Intel CPUs were victorious. But the technology industry was dissatisfied and always on the lookout for new sources of revenues. It launched tablet-sized computers in the mid-1990s, which flopped. Not so hand-sized PDAs, like the Palm 1000, which were hugely successful but hardly handy for CAD. The Palm’s wildly triumphant 2007 offspring, the Apple iPhone, initially sucked at tasks like CAD, but competition with Google’s Android ramped up the speeds of CPUs, the capacity of memories, and the resolutions of screens to make portable CAD possible on phones and the newly revitalized tablets.

Despite the obvious benefits, the portable CAD market never made it big. So Silicon Valley came up with new ways to make money: collaboration and the cloud. But what extroverted marketing departments didn’t understand was that engineers tend to be introverts who aren’t big on the whole “real-time sharing” thing. Collaboration remains embedded in CAD but tends to involve viewing and marking up drawings once nearly finished.

Ralph Grabowski writes on the CAD industry on his WorldCAD Access blog and has authored numerous articles and books.

Print this page

Advertisement

<