Get Your Motor Running

By Mike McLeod

CAD/CAM/CAE Autodesk Nino Caldarola StratasysHow Autodesk, Stratasys and a Canadian mechanical designer joined forces to create some of the world's largest rapid prototyped models.

You may not immediately recognize the name of Canadian designer and application specialist Nino Caldarola, but for anyone who’s been to either of the last two Autodesk University user conferences or read about them, you most likely know his design work.

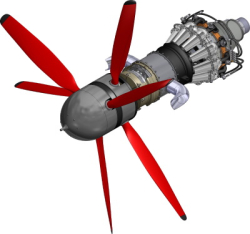

At AU 2008, the life-sized rapid prototyped model of his fire-engine red "chopper" motorcycle design became the iconographic focal point of the event. Similarly, the prototype of his twin turbo prop engine design stole the show at Autodesk University 2009. With its six spinning, 4.5-foot blades, it was impossible to miss sitting center stage during the manufacturing keynote.

But how those models ultimately ended up on a Las Vegas stage follows a winding path from the Winnipeg branch of Autodesk CAD reseller IMAGINiT Technologies to the CTO’s office at Autodesk corporate in San Francisco to the Eden Prairie, Minnesota facilities of Red Eye, the RP service bureau unit of Stratasys, Inc. Along the way, the three companies pushed the limits of their respective technologies and in-house talents to create two of the largest and most complex rapid prototyped models ever created.

Head out on the Highway

The story begins circa 2007 when Caldarola was working for then Autodesk CAD reseller CADCAM Solution (then a subsidiary of Bell Canada but now IMAGINiT Technologies Winnipeg branch). After a decade and a half working as an engineering technologist for transit bus manufacturer New Flyer Industries, agricultural equipment maker New Holland Canada and a stint at Pratt & Whitney Canada’s Mississauga facilities, Caldarola had accumulated considerable automotive and aerospace design skill.

But it wasn’t the work Caldarola performed during business hours that would earn him wider acclaim within the Autodesk community. After hours and on weekends, he began playing with ideas he had for a motorcycle design. According to Caldarola, the project was a way to test his own abilities and deepen his knowledge of Autodesk Inventor.

"The motorcycle started as a very simplistic tubular frame demo I created in Inventor 10 for a Winnipeg customer that builds bicycles for handicapped children," he says. "We got the business but I kept the data set."

After tinkering with that simple design to match the specs of a chopper frame he’d penciled out, Caldarola began adding wheels, forks and a 210cc V-Twin power plant–a hybrid of Harley Davidson’s Evolution and Suzuki 1500 engines. From there, he modeled the remaining hardware, experimenting with surfaces for the tank and seat and dabbling with the tubing and hydraulic line generators in Inventor Professional.

As the motorcycle assembly took shape bit by bit over two and a half years, people within Autodesk took a growing interest in Caldarola’s "hobby" project. Eventually, word of mouth brought the design to the attention of Gonzalo Martinez, director of strategic research in the Autodesk CTO’s office. At the time, Martinez says he had been researching the burgeoning 3D printing market and realized that while the technology had progressed, people’s awareness of its capabilities hadn’t kept pace.

"People see 3D printing in terms of very small objects but I thought, what if we tried to print something really big for Autodesk 2008," he says. "We asked for the rights to Nino’s motorcycle model and I started contacting the larger rapid service bureaus. The interesting part of the story is that we didn’t tell Nino we were going make the model."

Gonzalo approached his contacts at Stratasys business unit, RedEye On Demand, to see if they could output a full scale version of the model. With only two months to output the 10-and-a-half-foot motorcycle and assemble its 100+ parts in time, the crew had to put the company’s production facilities into overdrive.

"The challenge on the motorcycle project was that Nino had designed it as a concept rather than a model intended for rapid prototyping," says Brian Sabart, senior applications engineer, direct digital manufacturing, at Stratasys. "Since the chopper was intended to be made out of metal, we had to determine if the structure could handle its weight in plastic. In the end, we did have to put in two metal pipes down the front forks to add rigidity, but everything else was 100 percent FDM."

Over the next four weeks, RedEye ran a combination of six Stratasys FDM Maxum and FDM Titan machines non-stop to produce the chopper’s various assemblies from ABS M30 thermoplastic. In the final run up to AU 2008, the RedEye crew assembled the parts into the final model including articulating steering, illuminating headlights and rotating wheels before it was transported to Las Vegas for its surprise unveiling.

"I thought Autodesk was just going to use a rendering for display, but when they played ‘Born to be Wild’ and I saw my creation coming out of the ceiling, I literally fell off my chair; people thought I’d had a heart attack," he remembers. "Afterwards, I became the celebrity of the show. My little side project has blossomed to the point where I am completely stunned by the feedback I’ve gotten."

Taking Flight

As impressive and well received as the motorcycle had been, the 44-year-old designer hadn’t yet shown off his best work. Over the same three-year span that had seen the creation of the chopper model, Caldarola had also been devoting his free time to his true passion: an experimental turbo prop engine.

"That was another project where I wanted to challenge myself; to see if I could do something in Inventor that the higher-end CAD products were able to create," Caldarola says. "I’ve always loved jets and found the forms of those early post-WWII engines to be very intricate and industrial. So, for my design, I started delving into my old technical manuals and history books."

Caldarola says his engine design is composed of three general sections–gas generator, gearbox and the twin propellers themselves–each drawing on a different era of aerospace history. For the gas generator, he was inspired by historic Rolls-Royce and De Havilland engines combined with modern designs, particularly the Piaggio Avanti II aircraft engine.

"My turbo prop design is known as a free wheel turbine, meaning that there are two turbine wheels–one dedicated to the gas compressor and a second turbine dedicated to driving the propellers," he explains. "Because they aren’t physically connected, each rotates at its optimum RPM and in opposite directions which provides for a well balanced engine."

For the turbo prop’s double reduction gear box, he drew on the compact design of the Pratt and Whitney PT 6 series of the 1960s combined with the counter-rotational gear boxes of Russian military aircraft. Finally came the propellers themselves, the most challenging component to model, he says, due to their mid-blade twist. All told, Caldarola says there are more than 4000 parts in the final design, including all the components needed to manufacture a working engine.

"To create it, I went through every feature and function Inventor Professional has–not only the modeling portion but also the harnessing, tubing and FEA features," he says. "For instance, I had to make sure that some of the gearing was able to withstand certain loads, so I ran it through FEA analysis to make sure it wouldn’t start stripping teeth."

In the Spring following AU 2008, Caldarola approached his now friend, fellow aerospace enthusiast and former aerospace engineer Martinez with his turbo prop design. Stunned by complexity of the design, Gonzalo says he jumped at the chance to work with the Canadian designer again.

But with 4000+ parts, the pair quickly realized the turbo prop CAD model would need to be simplified. After a series of meetings with the build crew at RedEye, the team settled on a more manageable 188 part design that included all the exterior features, the complex gear box and an electric motor to set the 11.5 foot span of the blades turning.

"Over a four week period, we were able to build everything one time with no surprises," says Stratasys’ Sabart. "Considering the detailed parts in that assembly, particularly in the gear box, the tolerance stack-up could have introduced a lot of error potentially. However, the FDM systems can hold plus or minus .005 accuracy so, when you put the parts into the assembly, they are usually true to the original design."

As with the motorcycle the year before, RedEye’s build crew split the larger components of the turbo prop into small sections to fit the build space of their FDM machines. The smaller sections were then fused together using a combination of solvents and a plastic hot air welder that uses the FDM build material as filler.

"Once the seam solidifies, you’ve got solid plastic so you aren’t introducing a second material that could be the weak point within that bond," Sabart explains. "The process adheres the FDM material to itself so that the welded component becomes one solid part."

Overall, Sabart says the turbo prop took about six and a half weeks to complete from initially receiving the CAD file to completed model at a cost of approximately $25,000. While pricey, he says that pales in comparison to the nine-month construction time and estimated $800,000 price tag if they had used conventional processes. For Caldarola, the stir created by two physical prototypes, given their size and complexity, has created a new mindset.

"Because the materials that the engine was made from is on par with an injection moulded part, direct digital manufacturing is within reach if the technology can advance a little bit more," he says. "For me, this is a very exciting field and I just happened to have fallen smack dab in the middle of it."

Now that Autodesk, Stratasys and especially Caldarola himself have set the bar progressively higher, will they be able to top themselves for AU 2010? When asked, the team members are non-committal, but Caldarola hints that he may have a more ambitious project in the works.

"Let’s just say that I might have started working on a 1932 Ford Deuce Coup that I’ve always had an eye on," he says, "but there’s no telling what the future will bring."

www.imaginit.ca

www.autodesk.com

www.stratasys.com