Closing the Engineering Gender Gap

By By Dr. Mary A. Wells, PhD, FEC, P.Eng.

gender gap UniversityWhy women disproportionally opt out of engineering's education and career pipeline.

As we start 2018, I am reflecting on the past five years in my role as the Chair of the Ontario Network of Women in Engineering (ONWiE) and contemplating my new role as the Dean of the College of Engineering and Physical Sciences at the University of Guelph. In particular, I’m wondering what needs to change to close the gender gap in Canadian accredited engineering programs.

As chair of ONWiE for the past five years, I’ve had the privilege to report to the Council of Ontario Deans of Engineering (CODE). I can honestly say I have never met a group of leaders more committed to gender diversity in their engineering programs. In true engineering fashion, they want concrete steps and actions to “solve” the problem.

Unfortunately, the answers aren’t so clear cut. The barriers to closing the gender gap are related to implicit bias and gender stereotypes but also broader socio-economic, structural and sociological issues.

The recognition of the need for more women in engineering is not a social justice issue (i.e. “letting the girls play with the boys”). It resonates deeply within government organizations, professional engineering bodies, and academic circles as a value proposition that makes sense from both a business and innovation perspective.

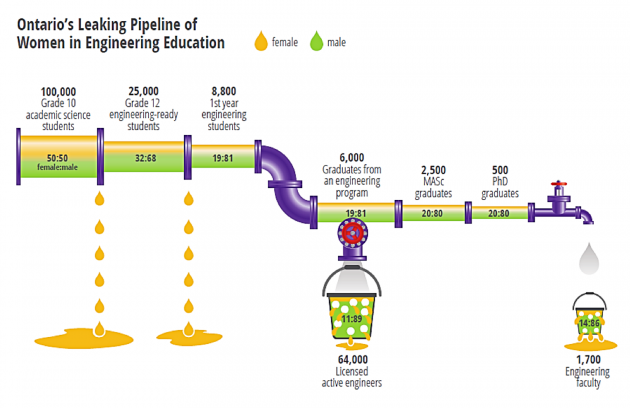

As part of my role as the ONWiE Chair, I have examined where we lose women in our engineering profession. I call this the ‘Leaking Pipeline’ and have summarized my findings in Figure 1. As you can see, it’s still an unusual choice for women to choose to study and stay in the engineering profession.

Figure 1. Ontario’s Leaking Pipeline for Women in Engineering. The ratios are the percentage women (left) and men (right) at different points in the pipeline. Developed using data from 2012.

One of the largest leaks in the pipeline is the high school years within the fraction of female grade 12 students I call “engineering ready” (i.e. they have taken the required courses to apply to an engineering program). Surprisingly, it is not the advanced math courses that cause this divide but rather Grade 11 and 12 physics!

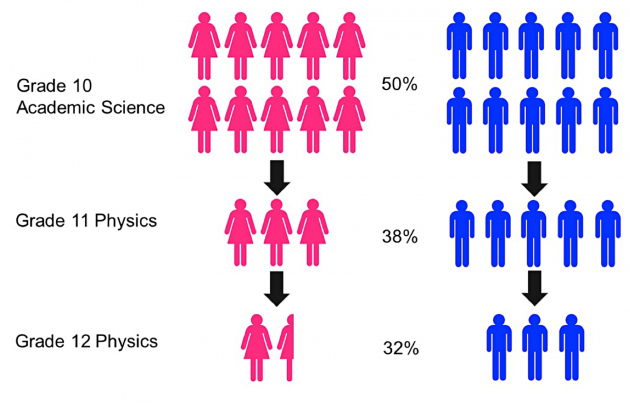

In fact, out of all the natural science courses offered in high school, physics is the least popular. The subject results in a 70% loss of male students from grade 10 academic science (a required course) to physics 12 and an 85% loss of female students (see Figure 2). Considering physics 12 is a requirement to apply to engineering programs in Canada, this has serious implications for the Canadian engineering talent pipeline.

In fact some schools and faculties of engineering in Canada are now actively discussing dropping the Grade 12 physics requirement as a way to open up the pipeline and create better gender diversity in the “engineering ready” pool.

From my perspective, this is not the approach we should take to tackle the gender gap in engineering. A better approach would be to work with high school science teachers, guidance counselors and the ministry of education to identify the reasons for this substantial, and gender skewed, drop in enrollment to develop interventions that would plug this critical leak in the pipeline.

The Ontario Network of Women in Engineering

ONWiE (www.onwie.ca) is the primary network through which the Ontario schools and faculties of engineering and science work to collectively address the status of women in engineering. This network was formed in 2005 as a key part of a collaborative impact plan to address the persistent low enrolment of female students in engineering programs across Ontario. This unprecedented collaboration is all the more significant given that these schools and faculties educate close to half of all undergraduate engineering students in Canada.

For the past thirteen years, ONWiE has provided a platform to work collaboratively on outreach programs directed at female youth. These have included programs such as Go ENG Girl (grades 7-10), Go CODE Girl (grades 7-11) and a Girl Guide STEM badge day program (grades 4-6). Key aspects in the success of the programs has been the use of engineering student and early career engineering professional role models and the involvement of parents.

I believe these targeted outreach efforts have made a substantive impact on the engineering landscape in Ontario and have resulted in measurable changes in the number of female students that chose to study engineering. One concrete example of this impact has been the change in the applicant pool to the Ontario engineering programs. Over this time frame, we have seen a tripling in the number of female applicants to engineering programs in Ontario. This change in the applicant pool has led to a steady increase in the participation of females in engineering programs across Ontario. In 2005, 4,814 female students were enrolled in undergraduate engineering programs across Ontario (17% of the engineering student population) versus 8,057 female students in 2016 (21.2% of the engineering student population).

As a result, many Ontario schools and faculties of engineering are now welcoming record high numbers of women in their 1st year programs including the University of Toronto and the University of Waterloo, two of the largest engineering programs in the country. I believe this is a direct result of the targeted outreach programs we have offered to girls and young women in both elementary and high school and this important work should continue.

In addition to high school curriculum, the other significant issue we need to address is workplace culture. From the aerospace sector to Silicon Valley, engineering has a significant retention problem. Currently, close to 40 percent of women with engineering degrees either leave the profession or never enter the field. As a female civil engineer said in a recent study:

“Women leave engineering due to a lack of job satisfaction, lack of reliable role models, inflexible work schedules, workplace discrimination and glass ceiling issues.”

Figure 2: Loss of male and female students in Ontario from Grade 10 Academic Science through to Physics 12 and the effect this has on the percentage of women in Physics 11 and 12.

If we hope to make substantive changes in the participation of women in engineering – workplace culture needs to change drastically.

Engendering STEM

I am very fortunate to be part of a new national research consortium called “Engendering Success in STEM (ESS)” which has received a $2.5-million Partnership Grant from the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. ESS is using this funding to break down the biases girls and women face in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) from early childhood through to early career.

The ESS consortium brings together academic researchers and STEM experts from across Canada to help develop and test interventions to foster support and minimize implicit gender biases for women and young girls in science and engineering. These interventions target the obstacles that are unique to each developmental stage on the pathway to success in STEM. Most importantly, the interventions are not designed with only girls in mind, but recognize that there are barriers presented by biases in both boys and girls. Boys and men play a very important role in welcoming girls and women into STEM and are a key component to broader cultural changes.

I believe this will be a game changer for the engineering profession and provide us with strong, evidence-based strategies to catalyze systemic efforts in outreach, recruitment and culture changes already underway. If we really want to close the gender gap in engineering, it is essential to ensure all girls and women feel they can belong in technical disciplines and are able to envision themselves having vibrant, fulfilling careers.

Dr. Mary A. Wells is the Dean of the College of Engineering and Physical Sciences at the University of Guelph and the Chair Ontario Network for Women in Engineering.