Extreme Mobility

By Mike McLeod

General ARKTOS design engineering Oil Sands vehicleB.C.’s amphibious Arktos Craft braves fire and ice to reign as the ultimate “go anywhere” vehicle.

In the 1980s, Canada’s big players in the oil and gas industry realized they had a problem. Operating an off-shore oil platform in temperate parts of the world was dangerous enough. But when the rig is located in the rich oil fields of the Arctic’s Beaufort Sea, evacuating the crew in case of emergency would be no trivial matter.

In the 1980s, Canada’s big players in the oil and gas industry realized they had a problem. Operating an off-shore oil platform in temperate parts of the world was dangerous enough. But when the rig is located in the rich oil fields of the Arctic’s Beaufort Sea, evacuating the crew in case of emergency would be no trivial matter.

For example, offshore structures like BP Exploration’s North Star Island—an artificial island off the northern coast of Alaska—are surrounded by rubble fields and miles of ice-infested waters. In case of an explosion or oil slick fire, the industry’s standard life rafts would be clearly inadequate. What they needed was an evacuation craft that could navigate the ice-transition zones of the Arctic Ocean, yet also carry 50+ passengers and cargo onto and over some of the most forbidding terrain on the planet.

With funding and technical input from a Who’s Who of oil and gas companies—including ESSO, Gulf Canada and Dome Petroleum—Surrey, B.C.-based Arktos Developments Ltd. (formerly Watercraft Offshore Canada Limited) began development of what would become the Arktos, a one-of-a-kind amphibious craft that redefines the concept of “go anywhere” transport.

But when you design arguably the world’s most mobile vehicle, you have to plan for all possible operating environments. That’s especially true, says Nathan Kew, technical supervisor for Arktos Developments Ltd. (ADL), when it has to protect its passengers from temperatures down to -50°C yet simultaneously survive the heat of an oil slick fire.

“Basically, the Arktos is built like a Thermos bottle,” he says. “Its structure is composed of an e-glass/Kevlar-hybrid composite sandwiched around a foam core, so it’s very well insulated. And because it is a composite structure and hollow inside, it’s relatively light and very stable on land or water.”

“Basically, the Arktos is built like a Thermos bottle,” he says. “Its structure is composed of an e-glass/Kevlar-hybrid composite sandwiched around a foam core, so it’s very well insulated. And because it is a composite structure and hollow inside, it’s relatively light and very stable on land or water.”

To prove its insulating effectiveness, the company engulfed the Arktos in flame for nearly 20 minutes at the Justice Institute of British Columbia Fire & Safety Training Center’s test pool. While the outside reached several hundred degrees Celsius, Kew says the temperature inside the craft rose by only one degree. In addition, he says the composite hull protects the craft from the abrasive and potentially crushing forces encountered while traveling through and over ice floes.

To traverse this rugged terrain, the Arktos looks similar to a tank or bulldozer, but Kew says the track system is also designed to maximize the vehicle’s interior space. Rather than a drive chain, the grouser tubes that comprise the track segments are mounted to a rubber belt and act as the chain, driven by large sprockets.

“We also don’t have bogie wheels or suspension other than the inherent flexibility of the hull,” Kew explains. “Instead, the track travels on a slider system which is only an inch and a half thick. That allows us to use the track carriage for the engine room, passenger accommodation and cargo space.”

In addition, the tracks are covered in spikes, optimally shaped and angled to help the vehicle claw itself out of the water and scale icy inclines as steep as 34-degrees.

For propulsion, each of the vessel’s hulls or units is independently powered by a 260 horsepower Cummins diesel engine. On land, the engines are linked, through hydraulic motors, to the tracks and propel the 15-metre long, 32-ton Arktos at speeds up to 16 kilometres per hour. On water, the amphibious vessel operates more like a very large Jet Ski. A water jet, combined with a 360-degree steer-able nozzle, propels the craft at speeds up to 5.5 knots.

“The diesel engines drive a set of hydraulic pumps and the power is distributed through a big logic manifold,” Kew explains. “That power can then be channelled to either the track system, the water jet or the ancillary consumers which control steering and articulation. We can also re-route the circuit to drive in combo mode—that is most of the power runs through the water jet and a portion goes into the tracks, to help make the transition from water to land.”

“The diesel engines drive a set of hydraulic pumps and the power is distributed through a big logic manifold,” Kew explains. “That power can then be channelled to either the track system, the water jet or the ancillary consumers which control steering and articulation. We can also re-route the circuit to drive in combo mode—that is most of the power runs through the water jet and a portion goes into the tracks, to help make the transition from water to land.”

It’s the transition, Kew says, that presents the greatest challenge and accounts for its dual hull design. A single unit, he says, reaches a certain angle as it climbs out of the water before it begins to claw away at the edge of the ice.

“But with the two hulls, the front unit uses the buoyancy of the back unit as a support, like getting a hand up on your foot,” he says. “When the front gets on land or ice, its tracks pull the back unit out of the water.”

To help that process, the Arktos’ two hulls are linked by a hydraulically powered articulation arm that allows each unit to operate at independent angles with three axis of motion. Articulation is controlled by the driver, giving the craft added mobility.

“If you are approaching an ice edge, the hydraulic cylinder on the articulating arm can pitch up, which pulls the forward unit’s front end up in the air and exposes the climbing surface of the tracks to the ice edge,” Kew says.

“If you are approaching an ice edge, the hydraulic cylinder on the articulating arm can pitch up, which pulls the forward unit’s front end up in the air and exposes the climbing surface of the tracks to the ice edge,” Kew says.

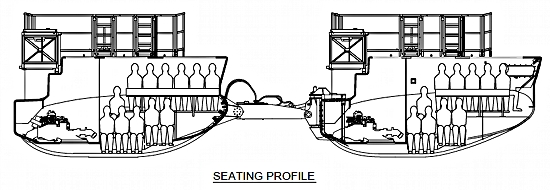

Currently, there are 25 Arktos Craft serving in remote locations around the world, including the North Caspian Sea, China’s Bohai Delta and the northern coast of Alaska. Most in the field serve as evacuation craft and are fitted with seating for 52 passengers, a fire fighting water cannon and a positive air pressure system to expel sour gas.

However, the company continues to expand on the original design for different applications. The Arktos MultiTask Craft, for example, was developed for the Albertan oil sands and features a crane and pontoons for added buoyancy.

“Currently, we are also working closely with one of the oil companies to do oil spill response,” Kew says. “Our task would be to carry response equipment to difficult locations other craft simply can’t get to.”

www.arktoscraft.com