A STEP in the Right Direction

By Ralph Grabowski

CAD/CAM/CAE Aerospace Automotive Metal FabricationSTEP file format makes strides toward becoming the PDF of machining and CAD data transfer.

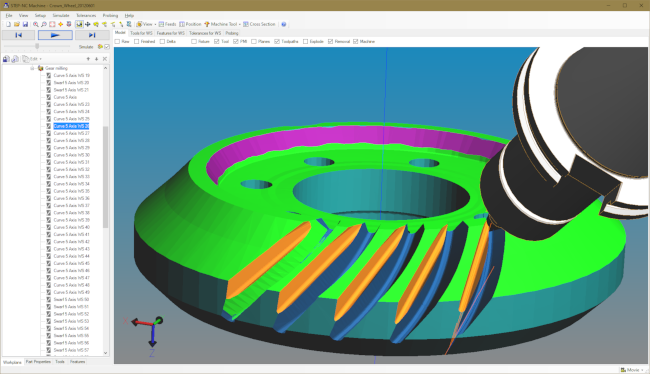

A STEP-NC file instructing the roughing, finishing, drilling and gear milling of a crown wheel with 105 operations and 925 tool paths.

(Photo credit: STEP Tools Inc.)

As IGES adoption increased, though, it also became unwieldy as it adapted to support data from an increasing number of MCAD systems. In response, the IGES steering committee started a new file format, PDES. “PDES is envisioned to support all aspects of product description, from initial conception through product design, manufacture, support, and disposal,” said the US Department of Commerce, describing what PLM sounds like today.

In 1985, the committee contributed PDES to an ISO initiative that had also initiated a universal file format designed to handle “anything from a microchip to a battleship.” This became known as the “STandard for the Exchange of Product model data” or STEP. In 1988, a group of aircraft manufacturers formed the PDES, Inc. consortium to oversee STEP’s development.

Defined by the EXPRESS data modeling language, STEP was designed to be extensible so that it could accommodate new technology. First released in 1995, STEP is sometimes referred to as “AP203” (level 2 application protocol).

Today, STEP consists of 800 standards, most of which compose a library of reusable definitions, but four are defined for end users. In addition to the original AP203 standard that defined solid models, AP214 added assembly data in 2003, AP242 added annotations in 2015 and AP242e2, released just last year, includes tolerances.

STEP for Machining

The original purpose of IGES was to make it easier for manufacturers like General Electric to deal with 3D models arriving from suppliers using incompatible MCAD file formats.

The process of machining a part from these files began with a CAD operator creating a drawing with no regard for the manufacturing process. A CAM operator would then design a manufacturing process and a CAM software post-processor generated the G-code to instruct the machine. A CNC operator then closely supervised the machining to make sure the initial parts were made correctly.

Since then, STEP has replaced IGES and has been extended into a machine tool control language, known as STEP-NC (numerical control). In 2005, AP238 version 1 was added to the STEP standard to incorporate precision machining. Last year, AP238 version 2 was added for precision assembly.

What’s more, the addition of AP242e2 tolerances allowed STEP to be useful in automated manufacturing. When you know the tolerances manufacturing needs to meet, you can machine parts to those tolerances. Before this, machines controls worked blindly, not knowing what was allowed.

Year by year, STEP-NC is adding more to the process data needed to know how to mill, drill or lathe a part, how to lead in, the speed at which to run and so on. The key is to know which operations have to be done in which order with the minimum viable tool path. When the data is rich, intelligent software on the control can figure out the rest.

According to Dr. Martin Hardwick, President and CEO of STEP Tools Inc., the desire today is to go direct from CAD to CNC. In this process, a CAD operator makes the 3D model suitable for manufacturing. A post-processor in CAD makes the STEP-NC file and a CNC machine uses STEP-NC for automated and optimized machining.

“Before, the operator figured it out; now, the software has to be rewritten to figure it out,” Hardwick says.

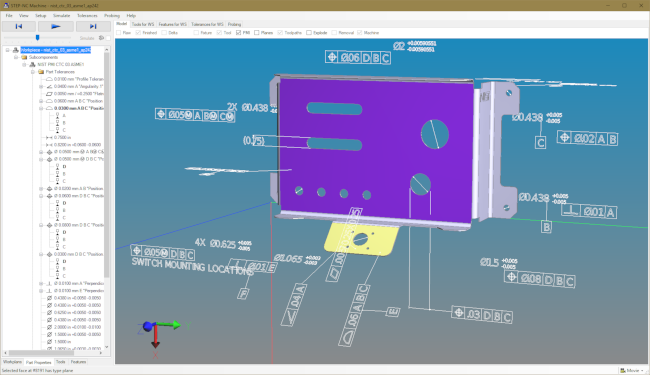

A NIST-created test file with AP242 presentation and semantic geometric tolerances.

(Photo credit: STEP Tools Inc.)

Since 2017, STEP-NC has been used to machine millions of 5-axis parts each year for commercial aircraft, such as the Boeing 787. Now STEP-NC is being prepared for direct-CAD-to-CNC 2.5-axis milling for features on airframes. As well, it is getting ready for 3D printing, leading Hardwick to call STEP-NC “the PDF of machining.”

ODA Expands to STEP

Yet, for all its advancements, integrating the breadth of STEP’s capabilities is beyond the resources of many CAD software developers. That’s a situation the Open Design Alliance (ODA) looks to remedy. The non-profit technology consortium is known for open software development kits (SDKs), such as for reading and writing DWG and PDF files. With these SDKs, members can create CAD software that is able to access and exchange engineering design data. By developing the code on their behalf, the ODA’s 1,200 members don’t need to develop it themselves.

Five years ago, the organization expanded beyond offering individual SDKs to also developing complete technology packages for CAD and BIM, (e.g. web collaboration, version control, visualization) on any platform, supported by a natively developed solid modeler and constraints engine.

Earlier this year, the ODA announced it’s also taking on STEP support as a long-term organizational priority. According to ODA president, Neil Peterson, the move was driven by demand from its members, since currently available STEP libraries are expensive and royalty-based. While some STEP software libraries have been released to the public domain, they suffer from insufficient development. As a result, there is no high-quality STEP library on the market that’s affordable for small CAD software firms, Peterson says.

Some ODA members just want access to STEP files. Others – who use the APIs ODA provides for the IFC architectural data model – want both: IFC for buildings and STEP for the machinery inside the buildings. According to the ODA, it will develop a full set of STEP tools by the end of 2022, including visualization, a free STEP viewer and web-based libraries.

Considering that STEP files, and the EXPRESS programming language, are hugely complex, I wondered how the work could get done so fast. The PDES consortium, which maintains the STEP standard, had been working on the problem for nearly three decades.

“We gained expertise by developing IFC,” Peterson says. “Similar to IFC, STEP is defined using EXPRESS schema, and so we can reuse the automation framework we developed for IFC to quickly build a high-quality STEP solution.” As well, the ODA says it’s working with PDES, inc. just as it works with buildingSMART on IFCs.

In detail, ODA’s timeline calls for the release of an initial STEP SDK with read/write for AP203, AP214 and AP242 (all conformance classes) by the end of 2021. By the end of 2022, it intends to release full visualization support for the three APs on desktop, mobile and web, as well as a free STEP viewer and the ability to convert to 2D/3D PDF, Navisworks, and DWG. Longer term, ODA envisions adding support for AP238 STEP-NC and the ability to convert to IFC and Revit. “Priorities in these areas,” Peterson cautions,” will be based on requests from our members.”

The cost of getting the STEP APIs from the ODA will be “free” to the ODA members who pay the annual US$1,800 membership fee, but no royalty payments are involved.

The MCAD/CAM industry needs a universal file format to minimize the cost and inconvenience of translating data. Arriving at universality is, however, a terribly complex problem, as CAD vendors want to maintain advantages over competitors by sticking with unique file formats. Lip service is given to data interoperability. Data flows easily into CAD systems, but emerges reluctantly.

The 2020s find the STEP standard expanding in two directions, towards greater complexity with STEP-NC, and towards lower cost with ODA STEP. The toolkits provided by the ODA, one can hope, ought to make implementing data exchange universality in mechanical easier.

https://pdesinc.org

www.opendesign.com

Ralph Grabowski writes on the business of CAD on his WorldCAD Access blog and weekly upFront.eZine newsletter.